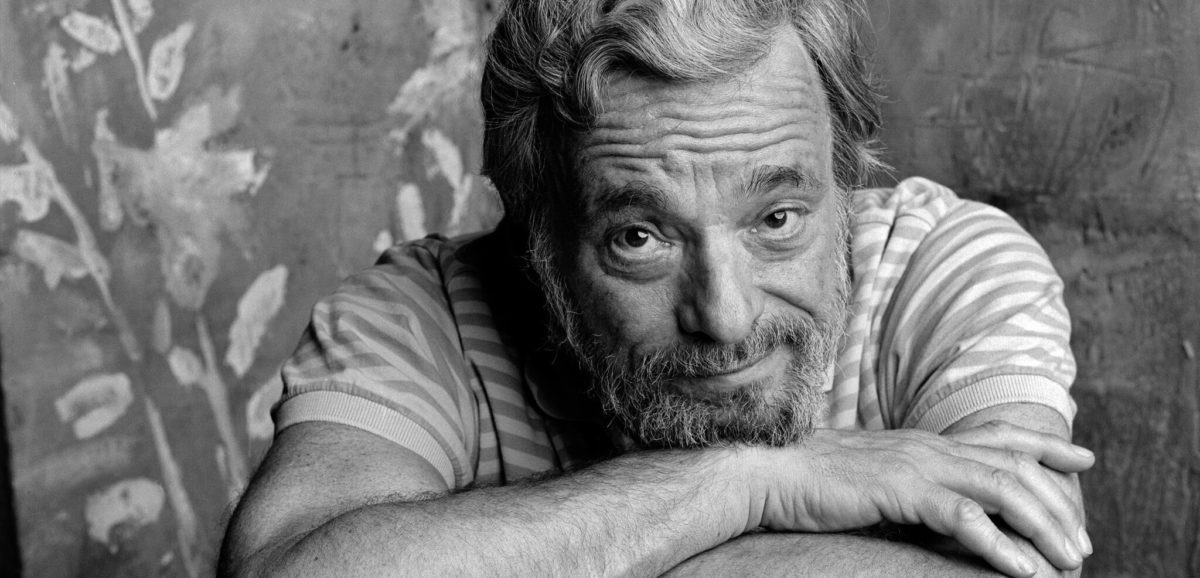

Photo Credit: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/26/theater/stephen-sondheim-dead.html

Stephen Sondheim, famed musical theatre composer, lyricist, genius, and a personal idol of mine recently passed away. His death has recently caused me to reexamine a thought I’ve had from time to time: that rides are akin to songs.

It might sound a bit strange at first to suggest that rides and songs are the most closely related storytelling mediums but consider their raw components. Music at its most basic level, stripped of lyrics, is a progression of sensations you feel. Rides at their most basic level, stripped of plot, are a progression of sensations that you feel. A simple unadorned coaster might be the equivalent of a single melodic line, one surrounded by scenery the equivalent of a full symphony: full of color, texture, and harmony. Both use these sensations to shape an arc of emotion within you — to tell stories. This is different than most movies, plays, books, and (many) games — which primarily use dialogue, plot, and prose. Those forms of storytelling speak to your mind. Music and experiences instead speak directly to your body.

Then there’s the form. Rides and songs both typically last 3-6 minutes, with some larger works venturing into the 15 minute range. Songs are extremely limited in the amount of time and space they have to convey information. Their stories must be precision crafted to their simplest essence to fit into such a brief form and to maintain clarity when put to a melody. Sondheim argues that because of this “every line has the weight of a paragraph”. Though he also cautions against confusing “simple with simplistic,” explaining that “there is a thin dividing line between economy of means and a penury of ideas.”1 I’d argue rides face the same struggles. The average scene length is a few seconds: enough for one visual and one line of dialogue.

Interestingly too, songs are seemingly endlessly repeatable. How many times have you listened to your favorite song? How many times would you go on your favorite ride again and again if you could? I’d wager those numbers are closer together than how many times you’ve watched your favorite film or read your favorite book.

Then there’s how they actually tell stories. Songs use music to bring the poetry of language to life. The core of the story and emotion is embedded in the notes, harmony, and structure themselves. The language sits on top and adds context. Similarly in rides, the emotion and story of the experience is embedded into the visuals and visceral energy of the ride itself, the plot adds context. The experience brings the emotions of the story to life. Story is used as an underlying structure that shapes the actual form as much or more than it does the overt content. Both songs and experiences recognize that story is fundamentally about ideas, not plot, and a story can be as simple as the feeling of optimism a good morning can generate, as in Oklahoma, or the feeling of optimism the hope of a better future can generate, as in Horizons. All it takes is some sort of beginning, middle, and end.

Sondheim had a fabulous anecdote about Oklahoma he would often tell about the difference between poetry and lyric writing and I think it also applies to the difference between writing for film/theatre and writing for experiences.2 He would point to “Oh What a Beautiful Morning” from Oklahoma and remark on Hammerstein’s lyrics:

Oh what a beautiful morning, Oh what a beautiful day, I’ve got a wonderful feeling Everything’s going my way

On the page they sound cliche, uninspired, and trite. But when put to music they soar. In fact anything more complicated might sound flowery or be difficult to understand. And it’s the exact same case with experience design for attractions.

I’d also argue that Sondheim’s own cannon of work overlaps a lot with the development of the dark ride as a storytelling medium, and in fact can be used to explain how it functions. Sondheim is famously one of the originators of the “concept musical”. For those unfamiliar with the terminology, concept musicals forgo a strict plot and instead the show focuses on a particular theme to meditate on.3 The plot, if present, is more of a framing narrative than anything else: device to go from scene to scene, each of which contemplates a different aspect of that theme. Concept Musicals are often quite dreamlike. The underlying logic is the connections between ideas rather than strict cause and effect. Shows like Company, Follies, Assassins, and A Chorus Line are all examples of this form. A form that is shockingly similar to many of the greatest dark rides ever made: The Haunted Mansion, Pirates of the Caribbean, It’s a Small World all easily fit this exact same description, right down to being musicals. They are concept musicals. Each is a collection of largely separate vignettes exploring a central theme, tied together by a vague framing narrative. It’s arguably THE formula for creating a Disney ride from 1964 to the late 80s. (Incidentally the concept musical and this variety of ride were both originated during the same time period in history).

I think this is, in part, the reason why music works so well in these types of attractions. It provides connective tissue: tying everything together and stating the theme in the process. Hell that’s why they’re called theme songs. And even many beloved non-musical attractions, particularly at regional parks, follow a similar “meditate on a theme” structure: Timber Mountain Log Ride and Calico Mine Train, Monster Mansion, Blazing Fury, Earthquake, and Droomvlucht come to mind as examples. The idea can also be applied to themed lands. Hell even most barebones rollercoasters attempt to do this by putting an evocative name on themselves. Rite of Spring might as well be called The Beast.

I think when creating attractions it’s easy to get carried away into an overtly plot focused frame of reference. That’s typically our reaction to the word “story”. I’m guilty of it myself. And it can result in amazing experiences. But it can easily lead to attractions that are jam-packed with cause and effect: only decipherable via flowchart. I’d urge all of us, particularly as we seek to create more immersive and engaging experiences, to remember how immersed you can feel in a piece of music, how simple yet engaging those stories can be. Think about how story can be used to heighten the visceral feelings and shape the awe of innate visuals into something meaningful. And vice versa. Don’t be afraid to let the audience marinate in a particular mood and restrain the plot to focus on it. Think of the concept musical.

Music takes life experiences that might only last for a few seconds in reality, and elongates them into experiences we can relish for minutes. It takes mundane thoughts and turns them into spectacular moments. That’s exactly what rides do, that’s what themed entertainment does: turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. I’ll leave you with one more bit of Sondheimian wisdom that seems particularly relevant to the world of themed entertainment:

“There are only three principles necessary…In no particular order, and to be inscribed in stone: Content Dictates Form, Less is More, God is in the Details — all in the service of Clarity — without which nothing else matters.”4

Stephen Sondheim

1 Sondheim, Stephen. Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 2010. 303-304.

2 Terry Gross, “‘Fresh Air’ Remembers Broadway Legend Stephen Sondheim (Part 2),” NPR, December 2, 2021, sec. Theater, https://www.npr.org/2021/12/02/1060848995/fresh-air-remembers-broadway-legend-stephen-sondheim-part-2.

See also

Stephen Sondheim Interview on Piano Jazz—1994. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApnynlakMPg.

3 “Concept Musical.” In Wikipedia, December 27, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Concept_musical&oldid=1062313404.

4 Sondheim, Finishing the Hat. xv.