In the last major essay on this blog I discussed an attraction that is commonly held to be one of the best dark rides ever made, Pirates of the Caribbean, and examined some of the techniques used that make it work so well. Today, I’d like to swing the pendulum in the opposite direction and look at one of the more ‘meh’ examples of dark ride design in the Disney library.

Under the Sea: Journey of the Little Mermaid, and in California, The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure are the long awaited ride adaptations of the classic 1989 animated musical that debuted as part of Florida’s new Fantasyland in 2012 and the revamped California Adventure in 2011. From here on I’ll just refer to them as ‘Mermaid’. For the purposes of this analysis I’ll be focusing mostly on the ride portion of the experiences as these are nearly identical between both coasts. The rides debuted to much fanfare from the Disney PR machine but have had a decidedly negative to, at best, ambivalent reaction among the fan and theme park community. To be clear, the rides are still of high quality and feature some dazzlingly technology, especially when compared to competitors, and many guests still find the experience enjoyable enough. But, I think it is fair to say that for a movie as iconic and beloved as The Little Mermaid the attraction that resulted, even for a ‘C’ or ‘D’ ticket experience as intended, feels underwhelming, and moreover, just off. Even simple dark rides like Peter Pan and Mr. Toad give better experiences. What is it?

Mermaid is, I think, the perfect example of what happens when all the effort in design is placed on aesthetics and little into experience. When story is crafted in a ‘premise’ sense rather than an experiential sense. It might also be an example of getting attached to a grand idea, then slowly chipping away at that idea to make it more practical, until the point is reached that really a different idea should be pursued altogether. But instead the original vision is forced into a container in which it can’t fit. There are several large scale issues that plague Mermaid. It takes a large character based story and tries to tell that entire story in a brief, environment based medium. The ride is burdened by the requirement it showcase all the songs from the movie and then uses a ride system ill suited for that requirement. It sets up higher expectations than it can deliver on (especially in Florida). It uses scarce resources to elaborate on specific moments and add exposition that it really doesn’t have the chronological budget for. After I examine these flaws I’ll suggest two different strategies to address these issues. One that would have been useful in development to avoid the issues altogether and a second that I see as a pragmatic way to better what is already there now without starting over.

Stuck in a Musical Loop

Musicals are tricky to adapt into rides for a couple reasons that all basically boil down to time. As I’ll discuss in a bit, often the best strategy to adapt a pre-existing story into an attraction is to focus on just one or two elements of that story and expand upon them for the attraction: creating something new and interesting yet familiar. Pragmatically, this is difficult when dealing with a musical, particularly if that musical is a popular IP. When kids and families go on “The Little Mermaid Ride” there is a perceived expectation (whether real or not) they’re going to want to hear all their favorite songs from the movie – which naturally leads to an obvious solution: the “book report” attraction. This is a term (to my knowledge originated by Imagineer Tony Baxter) that refers to an attraction that essentially summarizes the plot of the IP it’s based on. I’ll discuss the drawbacks of such an approach in more detail later, but in brief, it’s really difficult to tell a complex story that fills 90 minutes of screen time in a six minute attraction with any sort of the same impact.

This “requirement” to feature all the popular songs deeply handicaps Mermaid. Each song in the The Little Mermaid is at least as long as half the entire attraction! Most original attractions that feature songs almost universally take the approach of writing one or two main melodies that are then arranged and rearranged to provide a sense of continuity and congruence throughout the attraction and so that, in a medium where the average scene is 10-15 seconds, the song will actually feel like a song rather than an iTunes preview. And those that don’t have careful control over every moment of the experience. In contrast, songs in the best musicals will repeat and weave motifs in and out of the score but ultimately are purposely designed to contrast with each other. And they’re also deliberately designed to take one fleeting moment or emotion and expand it. This is certainly the case with the music Alan Menken and Howard Ashman wrote. In ride adaptations we’re often trying to condense, not expand. Trying to fit 20 minutes of drastically different styles of music into a six minute attraction while also trying to tell the full 90 minute story creates a real paradox.

Trying to include these multiple contrasting songs in one building and condensing each one to its shortest 15 second essence would be complicated enough but potentially doable. Say each song is carefully edited to length and plays in its own scene and those scenes are separated by soundproof doors and the vehicles are carefully timed so it all works (incidentally the approach Frozen Ever After uses at Epcot) or a new score is created from scratch and the soundtrack is contained within one ride vehicle (such as with Star Tours) but to complicate this even further, for reasons one can only assume have to do with capacity, Disney chose to use an omnimover style ride system for Mermaid. The omnimover is famous for being able to move large amounts of people per hour in its never-ending chain of vehicles. However, it is not famous for being able to move those people with any sort of chronological precision, or isolate any one space from another. Scenes in classic omnimover attractions loop and bleed into one another for this reason. Thus in order for Mermaid to work at all, the snippets of song must be played on loop, with no guaranteed beginning or ending. This causes several problems. One, Alan Menken writes songs that have very intricate emotional and musical progressions that move in one direction: these aren’t Sherman Brothers’ marches that easily cycle. The extracted snippets that result give recognizable melody but often suffer from a lack of useful information to move the story forward or the audience comes upon them at the end of a grand statement rather than the beginning.

Two, since the audio cannot be physically stopped by a barrier, large buffer zones must be created to transition between song scenes to prevent them from bleeding. Space is a scare resource in attraction design, and these buffer zones in the attraction utilize it poorly, functioning essentially as giant awkward audio crossfades. A problem that’s rendered more egregious by the relatively small building footprint the ride is working with. In a worst-case example a guest could potentially hear a broadway ballad fade in agonizingly slow motion right in the middle of the climax to the middle of the chorus of a hot calypso-ing crustacean band.

A Story Too Broad

As alluded to earlier, one of the main flaws of Mermaid as an attraction, is its ‘book report’ nature. While there is nothing inherently wrong with an attraction that just summarizes the movie it’s based on it does raise some potential risks – not the least of which is being dull and boring. Audiences have already seen the movie, they know what happens. While they love seeing the characters and environments they fell in love with, what they really want is to feel the way they did when they saw the movie while still experiencing something new. With simple movies and simple stories such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves or Peter Pan or Alice in Wonderland this is easier. You can pick one or two emotions that capture the essence of the experience and create an attraction that summarizes the plot through this lens. Notice even in these cases you’re not making a true summary of the plot, you’re making a biased summary that focuses on certain experiences and deemphasizes others to create the desired feeling in the guest. A true ‘book report’ ride, such as Pinocchio’s Daring Journey, does its best to stick to the plot of movie as close as it possibly can. The problem is that while it hits every beat, it cannot hit those beats in the rhythm of the movie. Thus the focus becomes telling as much of the plot in as short of an amount of time as possible all the while failing to recreate any of the actual story as lived experience. This is the problem that Mermaid runs into. The key to good adaptation from IP to attraction is focus. One could argue that the designers of the attraction attempted to make this focus music, but for the reasons listed earlier, the execution was problematic.

An Incorrect Medium

Another concern during adaptation is that of the medium of themed entertainment versus screen or page. The screen and page are ultimately character-based mediums. Stories are told primarily through the interactions of characters. Rides though, are much more environment, experience, or world based. While it is well understood that stories must be altered to best fit the medium say when adapting a book to a movie or a movie to a stage musical this seems to still be in the process of discovery in the world of attractions.The best adapted attractions come from properties that have elaborate interesting worlds, or unique aspirational moments, because then it is the world and the experiences within it that can be focused on. The Little Mermaid however, is not a film that really does a lot of world building. Audiences come away from the movie wanting to be Ariel or meet Sebastian not visit the ocean. Aside from being an remarkably popular movie there is really little about it that lends itself to easy adaptation so the deck is already stacked against the designers. There are some interesting visuals and aspirational experiences: King Triton’s castle, tall ships, a treacherous storm, and obviously being a mermaid but the ride doesn’t feature any of them because as long as we’re committed to telling the entire story from front to back there is no opportunity to focus on them.

Perhaps the most grievous example of this is that storm, which features prominently in the climax of the film. A swirling hurricane, Eric sailing that boat through the billowing waves, Ursula towering overhead. That moment is the most atmospheric and clearly environmental moment of the entire movie and yet is absent from the attraction. Or rather it is relegated to a tiny background diorama in a corner while a castle, kissing silhouettes, and pixie dust take up the foreground.

Mermaid is a character-based story trying to be told through an environment-based medium. To make matters worse the designers seem to recognize this but rather than try to adapt the story they instead try to shoehorn the ride into being a character based experience anyway. Indeed the ride might as well be called “the sophisticated sea-life characters animatronic exhibit” because that’s mostly how it’s structured. Extremely impressive animatronics of each character were built and then sets and props built to act as backgrounds for these characters. Then they’re strung together in chronological order, songs are played, and everyone calls it a day.

And that’s really the pervading issue with Mermaid. Each scene feels like it belongs more in a snow globe than in an attraction. They’re isolated events and a story is only told if you consciously fill in the blanks with the background you already know. And even if most of the audience can fill in those gaps because they’ve seen the film, audiences don’t want to. Much like children who will insist on hearing their favorite parts of a story again and again, despite knowing the details, the act of experiencing the storytelling is the appeal. Otherwise why would you be going on the attraction at all? You could just tell it to yourself and save $100.

Inefficient use of space and pace.

Speaking of telling a story: there is surprisingly little dialogue in Mermaid. If you have an attraction that is trying to tell the entire story of a 90 minute movie, and it spends nearly all its available time featuring songs that are specifically designed to stop the telling of the story – then well you have a problem. I’ve already discussed earlier how the choice to use an omnimover conflicts with the choice of using contrasting, time-dependent music. Long buffers between main scenes are required to isolate the sonic landscapes of each area, but those spaces don’t necessarily match up with the plot structure, which results in the transitions often being a bit wasted. Take for instance the example mentioned before occurring between ‘Part of Your World’ and ‘Under the Sea’. This long rock corridor between the two scenes is a dead-zone where no storytelling takes place largely because in the movie the space between the two songs is brief and the designers seem to have thought the connection between the two was self evident (Sebastian consoling Ariel). Here you have several conflicting problems.

1. The physical space in the attraction is being determined by technological needs, not by story needs.

2. That space is unfilled.

3. Without previous background information it is unclear how we get from Ariel moaning about not being a human to partying like it’s 1989.

A clear solution here is the addition of dialogue. It would go a long way to smoothing out the transitions between scenes and filling the dead air. In fact, in California this was actually done in one refurbishment with just a few phrases from Sebastian and it does help. But this still leaves several gaps behind. For a better example of how to approach a transitional space in the same attraction look no further than the entrance to Ursula’s lair where the sudden darkness and Flotsam and Jetsam’s leering stares and foreboding comments function as a perfect interlude between ‘Under the Sea’ and ‘Poor Unfortunate Souls’.

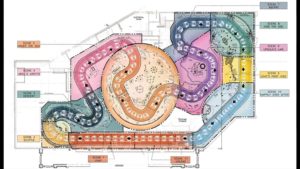

These instances of space dedicated to scenes not matching up to the significance in the story, and without respect to the resources at hand (building size) occur repeatedly in Mermaid. For example the ride is bookended by Scuttle introducing the story and wrapping it up. In the Pirates essay I outlined how important a proper induction is and this is one place where I want to admire what Mermaid is trying to do. I appreciate that the designers try to take time to bring the audience from the world of the theme park into the world of the story. The descent under the sea is by far the part of the attraction that seems to take the experience of storytelling most seriously. It works really, really well: gradually relaxing the guest and immersing them in the new environment. And I appreciate that Scuttle acts as a very clear demarkation of beginning and ending, even if I find it a bit superfluous and odd for a ride to literally tell you “we’re starting now and here’s everything you’re going to see”. Unfortunately this induction takes up a third of the attraction. It sets up a pace much slower than the rest of the ride will be able to maintain. It takes up space that otherwise could have been shifted, because, meanwhile, the majority of the plot of the movie is relegated to the last 1/4 of the building. And this is perhaps the most glaring issue of all in how Mermaid is constructed. It tries to tell a 3 act story logarithmically where Act One takes up 70% of the time, Act Two 20%, and Act Three virtually none at all. When riding it often feels like like the second half of the building was shaved off, and when looking at the track diagram it gives that appearance as well.

All the other issues discussed previously could be somewhat mitigated if not for the fact that the ride fundamentally fails to understand how the layout of physical space is inherently intertwined with time and therefore storytelling. It feels like the designers had these great ideas for a massive circular ‘Under the Sea’ scene and this really great ‘descent’ under the ocean and held on to them tooth and nail despite the footprint of the building dictating that such ideas would squeeze everything else to the side.

Style and Promises

One last thing to note before moving on to potential fixes. Mermaid has some odd art direction choices.

It’s an attraction that can’t quite seem to decide on what style of attraction it wants to be or even what style of art to use. There’s small examples: such as Triton’s hair being real despite every other character’s hair being plastic. And larger ones: such as the realistic seabottom of the descent versus the more stylized flat one of ‘Under the Sea’. Perhaps on a more meta level the ride, to borrow terminology from David Younger’s fantastic book Theme Park Design, can’t quite seem to decide if it is presentational or traditional. There are moments of fully immersive environments and other moments that heavily acknowledge they’re sets. Compare the descent or Ursula’s Lair to the last few scenes, the transitional moments, or under the sea: realisticly detailed representations versus highly stylized, somewhat symbolic sets. The problem with mixing such styles is the presentational elements will been seen as flaws rather than intentional. Combining these styles together creates confusion and discord. The problem is exacerbated in Florida with a queue design that is very new traditional and features an exquisite rock work facade, castle, caves, and interior spaces that contrast strongly with the more colorful, plastic, toy-like, and presentational elements within.

Florida’s queue also breaks what I consider to be a cardinal rule of entertainment design that I hope to explore further in another article. In entertainment one should always be in the position of underpromising and overdelivering. One should be deliberately setting expectations a few notches lower than you’ll actually deliver on. Thus the audience is always pleasantly surprised when they find out the ride is more elaborate, higher quality, has an extra scene after the finale, etc. Florida’s queue, by being as grand as it is and using the vernacular of scale and detail typically reserved for much more impressive attractions sets up expectations for a ride closer to Pirates, Mansion, Everest, or some other E-ticket experience in quality, duration, and scale than ultimately it delivers.

Alternative

So. What would an alternative attraction look like? What would an attraction with a similar budget, audience, capacity and “ticket” level be if the above principles were taken into account? Well to start with it would likely feature most of the music from the film or be an omnimover but not both. It likely would feature some familiar moments of the film, or offer an aspirational experience from the movie but not try to be the movie. It would try to offer something additional and unique apart from the movie. Perhaps you’re aboard a submarine or enchanted boat and you glimpse the story from a voyeuristic perspective. Perhaps you’re on a voyage through the ocean kingdom in a clam chariot pulled by seahorses. Perhaps, with a story that’s ultimately as simple as the essence of Mermaid is, a simple approach is best a la the classic Fantasyland rides. Indeed I suspect this is what the designers were intending to do, just when confronted with the capacity challenges a simple busbar attraction presents they moved on to a different ride system and tried their best to make it work. Maybe an segmented omnimover train a la Journey into Imagination or larger vehicles or indeed a larger or more well utilized building would have been a better decision.

Such a hypothetical attraction would also use a lens to condense the story in a cohesive way. The lenses that the classic Fantasyland attractions condense with – Snow White conjuring fear and suspense, Peter Pan wonder and joy, Toad silly zaniness – are the key to their successes. What lens should Mermaid use? I’d posit that the story is ultimately about longing, love and what one sacrifices for that. Perhaps put more simply: melodrama. Build the attraction with that lens in mind and the story beats select themselves: the longing Ariel feels for the human world, the anger her father reacts with, her exploitation by Ursula and the catch, falling in love with Eric, their fight against the forces that aim to destroy that love, and her ultimate perseverance. Note that ‘Under the Sea’ and Scuttle have no relevance to this lens. This doesn’t mean they have to be completely discarded, but it does mean that whatever role they play, if any, should be correspondingly minor. With a different lens, say that of Comedy, this could be different but then so would the whole selection of beats. Such a treatment would likely largely ignore Ariels desire to be human and the love story, it would certainly relegate Ursula to a background role, and instead focus on Ariel’s relationship with Sebastian, Flounder, and Scuttle and various hilarious scenes they get into. But such a lens doesn’t necessarily mesh well with the events of the story thus suggesting an original story with the same characters. With this framework in mind the selection of specific scenes can take place, without it, you’re left trying to be all things to all people.

Fixing What is There

The alternative proposed above is all well and good but it doesn’t do much to help what is already there. Remodeling the attraction to fit the beats above would only be possible by gutting the entire building, maybe preserving animatronics, and starting over. The layout of an attraction is so endemic to its story construction that it’s virtually impossible to rewrap one around another. Believe me I tried. It can be done at the extremes but it is a rather costly and impractical solution.

So what can be done? I think it is possible to, with relatively minor changes, reshape the attraction into something that while maybe not as great an experience as ideal, is a good deal clearer and more enjoyable than what is there now. I propose we do this by taking liabilities and turning them into assets.

Scuttle, for example, is one of the liabilities in the attraction. He’s a rather annoying, unreliable narrator, that doesn’t play any helpful role in actually telling the story. But we can make him have one by expanding his role. Another huge liability in the ride is the gaps in the story and awkward pacing. With so much music and so little time it’s difficult to know how scenes relate to one another, particularly as we get to the second half of the ride. But, we can let Scuttle do this work for us, thus both making him useful and filling in the gaps in the story. There is already ample dead space in the attraction, those transition zones talked about at length earlier, and these are the perfect opportunities for Scuttle, as our narrator, to actually fulfill his role and help us along, and even add comedy along the way. Imagine for a moment after ‘Part of Your World’ and in the awkward transitional space between it and ‘Under the Sea’ we hear Scuttle’s voice saying,

“Poor Ariel, she wanted to be human so badly and King Triton coming in there destroying all her dinglehoppers and thingamabobs – oh it was awful! No wonder Sebastian wanted to cheer her up! Or, uh, keep her from trouble.”

Something as simple as that fills up the dead air, gives the plot details we need, and keeps the audience engaged. And could be done in several ways: from adding onboard audio to the clamshells (my preferred, though perhaps still expensive solution), to adding directional speakers, or even through additional humorous figures. Can you imagine how hilarious it would be to see Scuttle, our hapless omnipotent narrator seagull, at the bottom of the ocean talking to us out of a diving helmet?

I think this technique would help a lot. I’d add him in this scene, perhaps a brief line during one of the duller moments of ‘Under the Sea’, again perhaps a brief line right before we see Ursula, during the transformation scene before ‘Kiss the Girl’, and absolutely during the climax – but more on that in a moment. And just as important would be rewriting the scenes he’s already a part of. Currently he just summarizes the entire story (badly) before you see any of it. Instead, have him set up the story.

I think additional legwork too could be done by rewriting existing dialogue/lyrics. To me the most obvious case for this is presented in the Ursula scene. ‘Poor Unfortunate Souls” is a great song, but it was written to tell the events of that section of plot in 5 minutes, not 5 seconds. But with a lyrical reimagining we could get a lot more information across than just how diabolical Ursula is, or the nonsense words of her spell.

You know the

Girl she says she wants to be a human

And folks she really doesn’t know I have a plan

Without her voice up there above

There’s no way he’ll fall in love

She’ll fail the deal, I’ll get her soul and man.

Oh that

Poor unfortunate soul

Distressed, naive

Oh King Triton will be squirming

When his daughter is a worm And

He’ll be mine then

Watch him grieve!

Those poor unfortunate souls

So brave, so nice

Foolish merfolk, their ambition,

Costs her voice, and costs his kingdom

What a pity

That’s the price

(Her crystal ball is filled with images of Ariel and Eric together as she stops singing and speaks)

“Three days to fall in love Hahaha! Fool! Being human was so important to you was it? I hope it was worth it. Hahaha” (Song Reprises)

You can see that with something like this more of the plot at hand can be related, while still getting to experience a classic song from the film. We can skip further ahead in the story, assume that Ariel has already transformed, and fill in some of the missing details.

Finally, something has to be done about the last few scenes of the ride. At the very minimum the ’True Love’s Kiss” scene needs reworking, but I’ll propose going a little farther than that. Admittedly this is where the plan gets the most expensive and ambitious but I think its still reasonable. I’d propose removing ‘Kiss the Girl’ and combining the spaces to form a larger climax scene.

Before this in the transitional space that is home to the current transformation animation, instead I’d place animation of surging waves and a storm rolling in complete with strobe and thunder effects. We’d hear Scuttle say something to the effect of “But they did fall in love in those three days and the sea witch was so angry! Eric set out to save Ariel before it was too late!”

Then in the newly enlarged space we’d have a sailing ship with Eric at the helm sailing straight towards Ursula as she is shouting “I will rule all the Oceans!” and so forth. Lightning, thunder, and dramatic music. We’d move into a dark space as we hear Ursula scream “Noooooo!” and perhaps experience a smaller ‘True Love’s Kiss’ before heading into the current final scene.

The swapping out of such scenes would be a compromise, but I believe fundamentally alter the ride for the better, adding excitement, thrill, a more complete story arc, cohesion, and dramatic tension to a ride sorely lacking in them all.

Conclusion

And that’s what’s wrong with Mermaid and how to make it better. Again, it’s not an awful attraction, especially when compared to the themed entertainment world as a whole, but for a movie with such resonance across the ages it deserves more. And if it weren’t for some poorly thought out decisions the attraction that we have today could have been so easily better. Crucially the ride system must match the type of experience you’re hoping to deliver in themed attraction design and stories must be condensed with a proper dramatic lens to provide an experience that still feels complete. Rides tell stories through environments and experiences, characters merely inhabit them so when adapting character-based stories into attractions it’s crucial to do it through the environments and experiences that can convey similar dramatic tension. Entertainment experiences should under-promise and over-deliver. Every square inch of an attraction should be utilized to tell a story and care should be taken to avoid designing scenes and physical space without regard for how such use of space will affect the overall pacing of the attraction or remainder of space in the site. With these ideas in mind attractions can be designed that better engage the audience, make more out of less, and overall create an experience that goes more swimmingly for everyone.

I enjoyed reading this article! I haven’t been on the Ariel Ride, mostly because my friends weren’t excited about it and we ended up not having the time. If the designers had foreseen, considered, and fixed the problems you mentioned (some I was surprised at… what were they thinking?) people would be more into it. The Little Mermaid definitely deserves more thought, a better ride, than it has currently. Your “fixes” sound good too!